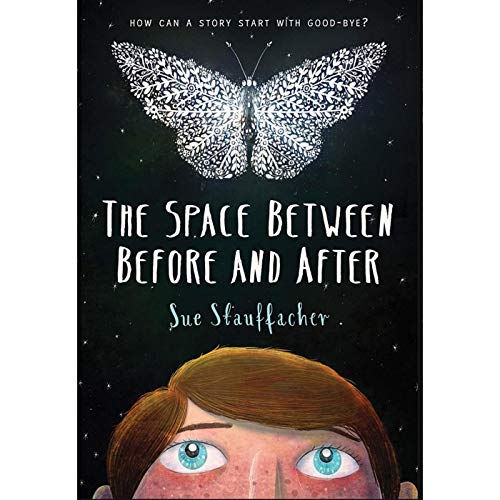

Last year, I narrated The Space Between Before and After by Sue Stauffacher for Live Oak Media. This beautiful book about grief, mental illness, and family features young Thomas Moran, whose mother has recently disappeared, his two closest friends, his complicated father, and his compassionate, elderly neighbor, Mrs. Sharp. Drawing from her own experience as a child in Nazi-occupied Hungary, Mrs. Sharp helps Thomas find a way to make sense of his loss and move forward through grief.

Last year, I narrated The Space Between Before and After by Sue Stauffacher for Live Oak Media. This beautiful book about grief, mental illness, and family features young Thomas Moran, whose mother has recently disappeared, his two closest friends, his complicated father, and his compassionate, elderly neighbor, Mrs. Sharp. Drawing from her own experience as a child in Nazi-occupied Hungary, Mrs. Sharp helps Thomas find a way to make sense of his loss and move forward through grief.

I was so moved by the story — its honesty and vulnerability, its courage in telling a story about a child’s pain — that I wanted to have a conversation with Sue about her experience writing it. It felt appropriate to share this conversation during the week of Valentine’s Day, when we celebrate the power of love and relationship in all its forms, whether that’s love between partners, friends, or communities. No book better exemplifies the mysterious power of love than this very brave and important narrative. I hope you’ll spend time with the interview and with the book.

Q: What was the inspiration behind this unusual book?

A: In 2012, a friend of ours disappeared in a similar manner to Thomas’s mother. Though the details of her story are not the same as Thomas’s mother (my friend was not depressed, for example, and her children were adults), I began to imagine what is was like to lose someone and not know what had happened to them. Also as a hospice volunteer I became aware of the need for age-appropriate responses to children struggling with grief. Like most of my books, The Space Between Before and After grew out of concerns I have for children’s well-being.

Q: What writers of children’s work inspire you?

A: My inspirations are old ones—Mark Twain, Roald Dahl, Zora Neale Hurston, Frances Hodges Burnett. These are writers who do not sugar coat. They believe children can handle difficult subjects. I know as a child, I could. And I appreciated the way they introduced the larger world to me.

Q: What books did you read as a child? Did you have an “UnderLand” (space under the bed that Thomas goes to for comfort and a transporting place to story)

A: Books I read and loved and had an enduring effect on my work, include: Where the Lilies Bloom, The Secret Garden, Heidi, Huckleberry Finn, Charlie & the Chocolate Factory, Their Eyes Were Watching God. Growing up in the 60s and 70s, parents were not encouraged to build libraries of books for kids as they are now. But I was obsessed with books and I treasured the ones I owned. My hidey-hole was in the back of the station wagon. I let my sisters have the back seat and insisted on being packed in with the luggage in a nest of my own with my books. And I LOVED fairy tales. I had a book called A Children’s Treasury of Folk & Fairy Tales, which I have since found again. This is what I was thinking of when Aunt Sadie gave the book of fairy tales to Thomas.

Q: Tell me about your decision to weave in the history about one of the greatest losses of the 20th century—the murders in Hungary in 1937—prompting Mrs. Sharp’s parents to leave, and then the Nazi occupation.

A: It’s consistent with my work that I like to bring attention to little-remembered moments in history. There were such huge atrocities in World War II that we tend to focus on the grand scale. But I like to remember and commemorate the small, independent acts of defiance as well. There were so many of them, and the bravery these people displayed is inspiring.

Q: Themes in The Space Between Before and After include social justice and grief. Mrs. Sharp’s own father was disappeared, Thomas’s mother disappeared. How do these two things link? Are these preoccupations in your writing in general?

A: I think the link between Mrs. Sharp and Thomas is less about the circumstances surrounding their respective losses and more about the losses themselves. As human beings, there is something terrifically comforting in knowing another person has experienced a similar situation to the one we’re struggling with. I’m tremendously heartened by organizations like Ele’s Place (here in Michigan) that provide non-denominational, age-appropriate grief services to children and teens. Kids can’t always articulate what they are feeling and thinking, and they don’t have the capacity always to rationalize what has happened. It can be lonely and frightening and create bad mental and physical health outcomes if their grief is untreated. Mrs. Sharp draws attention to the fact that, due to his age, Thomas needs another way to process his grief. It’s the beauty of having a wise elder in his midst.

Grief and social justice are, indeed, two enduring themes for me. They can be found most prominently in my books Donuthead and Harry Sue. Another important theme is that of connection, reaching out and forming communities. There are numerous studies pointing to the fact that young people feel more isolated and lonelier than ever. So many families close up around mental illness when they need to be reaching out. My hope is that this book can be a sort of road map, showing readers that while they go about it imperfectly (as most of us do), Thomas’s family reaches a place of authentic connection with others and sets the stage for healing the best they can from their tremendous loss.

Thank you this interview. Its heartening to see people aware of and doing something to help with other’s pain, especially children’s. Too often their pain is discounted or dismissed. It is always good to be reminded of the power of words and how they can heal.

Thank you for reading it, Colene. I agree.

I hope you are writing, too, dear friend. The world needs our stories! xo